FDR’S WHEELCHAIR … ESSAY #2

I asked a former daughter-in-law of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt how kids reacted when hearing her last name. Usually, she said, they would ask, “Oh, like Roosevelt Avenue?”

WHO OWNS HISTORY?

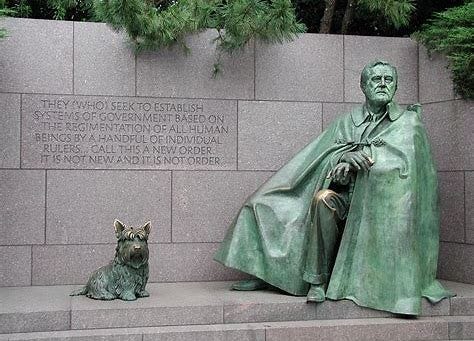

Wednesday, January 10, 2001. It was breezy, cold, and clear on Washington, DC’s National Mall as President Bill Clinton unveiled a life-sized bronze statue of former president Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR) seated in a wheelchair. The sculpture was a very late addition to the popular FDR Memorial that originally did not reveal his disability.

Like most city kids born “before air conditioning,” summer was not just hot and sweaty, it was scary. Even scarier than World War 2.

Debilitating and often deadly Polio was hiding in the atmosphere, in the pool water, on a store shelf, in the cool air of a theater. Was the girl across the streetcar aisle who just coughed going to infect me? My friends and I knew that Polio, quietly and randomly, was ready to strike, maim and kill, and that it also was named Infantile Paralysis.

Each summer’s Polio epidemic appeared to be worse than the last. Newspaper photos and then TV reminded us of the many children and a few adults clinging to lives in Iron Lungs to help them breath. Posters told us not to mix with new groups, not to get overtired or chilled, and to keep clean, especially to wash our hands.

It wasn’t until 1955, ten years after FDR died, that a vaccine to prevent Polio was available.

While FDR was open about being a Polio survivor he successfully concealed his skinny paralyzed legs from us. Roosevelt had to wear ten pounds of braces on those limp limbs (hidden by wide pants) to stand up. He could not walk, nor could he waddle, without strong people holding him up on each side, often they were his sons.

At that time, most people with severe disabilities were shamed, shunned, and sometimes hidden by their families. Even if they were smart, they were seen by many as mentally deficient.

That certainly wasn’t an attractive situation for an aspiring politician like Mr. Roosevelt. In part by hiding his paralysis, FDR went on to be Governor of New York and the US president.

The press totally covered up his disability and FDR was able to own his history for decades, even after his death.

Fast forward to the 1990s. As mentioned in the first essay on FDR’S WHEELCHAIR, one of my clients was the National Organization on Disability (NOD).

Forty years after President Roosevelt died, and after a lot of phone calls, I could locate but one photo of FDR in his chair and it hadn’t been published. The picture shows him, holding his dog Fala, and a little girl standing at his side. If you look online today you will find that very few FDR wheel-chair photos have since surfaced. Only this year (2018) a few home movies emerged.

NOD had commissioned surveys dealing with disability issues. They confirmed that most people with disabilities, whether severe or not, were depressed. Most didn’t seek education or jobs for which they were qualified.

As NOD’s communications consultant I was one of the strategists mulling over the best way to follow-up the surveys. The initial goal was to develop a nationwide campaign to encourage people with disabilities to seek jobs for which they were, or could become, qualified. We also sought a simple message for employers about the unexplored abilities within the disability community.

It was decided the FDR story was what we wanted to tell … the story we had to tell. And that he must be seen in a wheelchair to clearly illustrate his inspiring story and visually represent our motivational messages.

At that time there was a small buzz about a large FDR Memorial set to open in 1997 on the National Mall in Washington. There would only be one tiny indication that the man who led America out of The Depression and through WW2 did all that in a wheelchair. The hint would be behind a statue of him seated. FDR would be seen wearing the large cape he used to hide his wheelchair in public. If a visitor could squeeze around the back and look down, there would be two small casters peeking out that might indicate they were attached to his chair.

The NOD campaign to add a new statue, we hoped, also would open more positive discussions about disabilities than the highly divisive debate surrounding the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

(Having earlier been deeply involved in national controversies, I cautioned that our little cabal was about to occupy the lead car of a wild roller coaster. Among them was, ZIP Code’s introduction in the 1960s, while AT&T was strongly pushing its all-digit dialing. This led citizens and editorial writers to claim we all would just be faceless numbers. Like FDR’s wheelchair, it also involved facts vs. emotions.)

One ambition was to accurately position NOD as being smack in the middle of the national and rational center. A slew of historians, men and women “on the street,” and editorial writers attacked NOD for going against a beloved leader’s wishes. It was hard to get traction because NOD did not include the activists who were eye-candy for TV and tabloids by yelling and chaining themselves and their wheelchairs to the White House fence.

Across the country, and especially when kids started sending small contributions, a minor momentum for the statue and an examination of disability issues emerged.

Then, unexpectedly, a steady stream of very senior print and broadcast reporters and columnists wanted to visit with NOD’s president Alan Reich, the chief architect of the strategy and tactics. Usually, they would rather humbly introduce themselves and tell him about a close friend or family member with a disability and that was the reason they sought to know more about the issues.

I think their reports and columns about the real problems and potential progress of their own and others’ kith and kin were what turned the tide. By the time a statue was commissioned NOD had raised over $1.5 million for the project.

FDR’s surviving family, however, posed a serious roadblock that took a huge amount of our time. To hide-or-not-to-hide, that was their question. To honor Franklin’s wishes or honor his grit and abilities while in that darned chair. For months there was no consensus. The Roosevelt family’s very public differences revolved around the question of “Who Owns History.” Eventually, most supported the statue and what it stood for.

Since Fake News has entered public discourse, the question of ownership of personal and governmental history is more relevant than ever. The typical answer is “the winners own history.” That probably was true in the past. But now, any individual or organization with a smart phone, can try to shape what others, or history itself, will think of them. (This essay, for instance.)

NOD won a battle, maybe it was just a skirmish, but the outcome was perceived as positive. Even though it took over a half decade between our first planning session and the statue’s arrival on The Mall, America and those with disabilities were inching forward.

Addenda

“Once you’ve spent two years trying to wiggle one toe, everything is in proportion.” — FDR, 1945

- Michael Deland, chair of the NOD’s board of directors, had worked in George H.W. Bush’s White House as chairman of the President’s Council on Environmental Quality. I remember, Deland saying, that the alterations made for Roosevelt made it a great working environment for a person like himself in a wheelchair. Michael did have a way with words.

- The atmosphere at NOD was alive with the sound of big thinkers. Three of the most able were in wheelchairs Reich, Deland, and Jim Brady (former Reagan spokesman, then a NOD VP). Also, weighing in was Bernie Posner who for a long time he had been the top federal bureaucrat dealing with disabilities. Through no fault of his own was Bernie was Steven Spielberg’s uncle.

- And Marty Walsh, a fundraiser and promoter previously with United Way of America. Marty sent me an email about his intelligence gathering. “I was able to talk my way into a secret office on the top floor of a Senate office building where the planning of the FDR Memorial was underway (and had been funded annually by the Senate since 1964). I posed as a curious out of town visitor wondering why there was no identification on the door … talked my way inside and saw the time line and layout of the Memorial (to be) built. There was no plan to show FDR in a wheelchair.”

- Another sharp strategist was NOD’s Ginny Thornburg. Her crusade to make places of worship more welcoming has brought brighter lights so attendees can read the prayer books, ramps used by people in or out of wheelchairs, and among other things, sound systems loud enough that parishioners can finally hear what the Hell is being said.

- Today, because of the ADA, common sense, and new attitudes, there are advances in the lives of people with and without disabilities. Among the minor benefits are; mothers pushing strollers into crosswalks use the curb ramps and no longer wake babies with a thump at every street corner, doors automatically open for fathers with hands full of grocery bags, emergency signs have large, readable type.

- While many disabilities may not be immediately evident, families, employers, and individuals are more open about them. Many businesses now are mining the mother-lode of previously hidden talents. I recently heard that, at one point, half of a huge west coast sportswear company’s in-house designers were dyslexic.

(end)

No comments:

Post a Comment